- Home

- KD McCrite

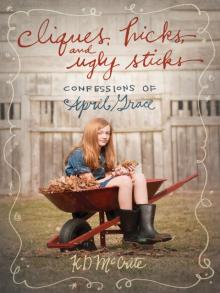

Cliques, Hicks, and Ugly Sticks Page 6

Cliques, Hicks, and Ugly Sticks Read online

Page 6

“You girls were going to do some math homework, I believe,” Mama reminded us.

Melissa and me exchanged looks of severe torture.

“Let’s get it over with,” I said bravely.

“Yeah.”

We picked up the Yahtzee cup, the dice, the nubby little pencils, and the score pads, put them all back in the box, and dragged our pitiful selves upstairs to sit in the middle of the floor of my bedroom and work on that awful, horrible homework assignment.

“April Grace,” she said before we started, “your mom does not seem one little bit different than usual.”

“I know she doesn’t right now, but she has been.” And I told her about Mama being cranky then sweet, and about her being tired and sleeping a lot.

“You know something?” Melissa said, staring thoughtfully into space. “They say kids go through phases, but I think mothers do, too. Mine sure seems to. Like right now she’s in a knitting phase, and she’s bought more yarn than you can shake a stick at.” She looked at me. “I think your mom is just going through a phase.”

There was a little flicker of hope in that statement.

“I sincerely hope you are right and she gets over it soon.”

We settled down then and got to work on that math.

“You want to know what I think?” I said at one point.

“What?”

“I think anything that says 5(x+2) = 25 should be illegal,”

I told her. “What is wrong with two plus two equals four, I’d like to know? Junior high is bad enough, but why do they have to make it worse by torturing us with this stuff?”

“I don’t know. But going to school in that rotten old building with only one restroom for all us girls is bad enough. It should be illegal. And I think gym class should be outlawed, too.”

“Me, too. Especially when Coach Frizell is our teacher. Of course, next semester Isabel is going to be teaching physical education. At least that’s what they’re calling her dance class.”

“That doesn’t sound like a barrel of laughs,” Melissa said, “but it’ll be better than relay races and sit-ups for the whole period like it is now.”

“Yeah.”

Neither one of us said anything for a minute. Then I came up with something else.

“I tell you what else ought to be outlawed in our school. J.H. Henry and his hair. He looks like he has been severely beaten with the wrong end of an ugly stick.”

She giggled. “Yeah. And what about him wearing shoes with no socks?” she added.

“And him calling me ‘babe’ and ‘foxy baby’ and ‘sweet red’ and trying to sit next to me in every class and making those awful goo-goo eyes.”

“I think he’s in love with you, April Grace.”

Now, right then I think I saw spots in front of my own eyes at the mere mention of such an awful thing. “Do not ever say that again, Melissa Kay Carlyle.”

“But it’s true. If it wasn’t, he’d not always be winking and grinning at you.”

“He makes me sick!” I hollered. “One of these times, when he points his finger at me and says, ‘Hiya, hot stuff,’ I’m gonna urp on his sockless feet.”

I thought Melissa was gonna have hysterics right there in my room. “If you did that, I bet he’d stop bothering you,” she said.

“Then I’m gonna do it!” I declared, not really meaning it, but I figured it might just be worth the mess to make that boy leave me alone.

Pretty soon, Melissa looked up from that stupid math book and asked me, “Does 5(x+2) = 25 make a lick of sense to you yet?”

“Not a single lick.”

I have to say, my friend and I would probably have had more fun if we’d had our teeth extracted by the dog dentist.

EIGHT

Mama Reveals Her Secret at Last

In Sunday school the next morning, Miss Chestnut went on and on about the wonderful privilege for us young people to be involved in this year’s Christmas pageant.

“You gonna be in that pageant?” Melissa asked me during the break between Sunday school and church.

“Nope,” I replied with all the confidence you can imagine.

When it was time for the service to begin, Melissa and I settled down in our usual pew. The choir had barely started to file in when Daddy and Mama stood up from their seats. Mama looked pale. It seemed like most everybody noticed them as they walked out of the sanctuary. I jumped up and went right after them.

“What are you doing?” I said out loud in the vestibule and did not care who all heard me. “Where are you going?”

“Mama’s feeling a little queasy, so I’m taking her home,”

Daddy said quietly. “You ride home with Grandma.”

“But—”

“I’m all right, honey,” Mama said, “but my stomach is upset, and I think I’d feel better lying down at home.”

“I’m coming with you.”

“Don’t argue, honey. Just do what your daddy said, and we’ll see you as soon as you get home from church.”

I could tell that if I said more, she’d feel worse, so I just nodded and watched them walk out the door. Then I stood at the door, cracked it open, and watched as they drove away. I just stood in that vestibule for the longest time. Pastor Ross was probably halfway through his sermon before I went back into the sanctuary and settled down on the back pew.

When we got home, I ran straight into the house and up the stairs to the room Mama and Daddy shared while Ian and Isabel stayed in the big master bedroom downstairs. Myra Sue followed me in a more ladylike fashion than the galloping flight up I’d taken. Mama was lying there in bed, her eyes closed. She was all pasty white. Even her lips looked pale.

“Mama?” I whispered.

She opened her eyes and gave me a weak smile.

“I’m okay, honey.” She looked past me at my sister. “You girls run downstairs and help Grandma fix lunch. I’ll be right as rain before long.”

“You promise?” Myra Sue asked.

“I’ll do my best.”

We both gave her a kiss on the cheek and quietly went back downstairs. Daddy and Ian were helping Grandma in the kitchen.

“We’ll set the table,” I said, and Myra Sue nodded, and that’s what we did.

Mama said she didn’t want any food right then, so she stayed in bed. Isabel actually hobbled with her crutches to the table and ate with us for the first time since she’d gotten home. Guess what? That woman did not utter one complaint. I think she realized she was not the only fish in the fishbowl that day and that sometimes other people are more important than her own personal self.

“I hope Lily recovers soon,” she said, and not one person disagreed with her.

I’ll tell you something. That was the quietest Sunday dinner the Reilly house had seen in a long time—maybe in forever.

Later, Isabel scraped and stacked the dirty plates from where she sat. When she finished, Ian helped her up and led her down the hall so she could go back to bed. Of course he stayed right there with her.

Myra Sue and I cleared the table. As we carried those plates from the dining room and into the kitchen, I realized that my sister and I had done this exact same thing the week before because Mama hadn’t felt well last Sunday either.

Maybe I should have felt better when, after we got the kitchen all cleaned up, Grandma announced she was taking a Sunday ride with Ernie Beason. You see, I knew Grandma would never go off that way if anything was seriously wrong. And the fact that Daddy said he was gonna go take a nap should have been enough to prove he wasn’t all that worried. But I was still scared.

I went outside and sat down on the top step of the front porch. Good ole Daisy lumbered up the steps and sat on the porch next to me. She leaned against my side and breathed her warm, damp doggy breath all over my head and face and looked at me with her brown, understanding doggy eyes.

I tell you, I dearly love that dog. I slung one arm around her fuzzy shoulders and buried my face in her fur. I could feel the motion of

her big body, which meant she was wagging her tail in sympathy.

“If you knew what was wrong with Mama, you’d tell me, wouldn’t you?”

I pulled back and looked at her, eyeball-to-eyeball. Her wet tongue slid right across my cheek, nose, and part of my upper lip. This time I didn’t even wipe away her canine kiss. I just hugged her up to me real tight.

“Daisy,” I said to her, “I just don’t understand why people can’t be as understanding as dogs.”

“April?” Myra Sue called softly.

She was standing on the other side of the screened front door, looking sadly at me. “Will you come in so we can watch a video together or something?”

“I’m talking to Daisy right now.”

Her lower lip trembled, and not in the pouty, put-upon way she always tried when she didn’t get her way. A big tear slid right down her cheek. “I don’t want to be by myself right now. Please?”

My sister doesn’t usually want to be with me, whom she has often called a brat, a dork, a geek, and the pest of the South. The fact that she asked me to spend time with her right then just proved she’s human after all. I’ll be purely honest with you: there have been many times when I’ve questioned that.

“Okay. But Daisy is coming in with me.” I might be good company for Myra Sue right then, but Daisy was good company for me. “And I don’t want to watch a video; I’d rather read. I’ll read out loud, and you can listen.”

“Okay,” Myra said, holding open the screen door for us both. “Shall I fix us some lemonade or something?”

Any other time, I might think this was a trick and that she’d give me something disgusting, like Kool-Aid made with vinegar, but I knew that wouldn’t be the case this time.

“Okay. And let’s give Daisy a drink, too.”

“But not lemonade,” Myra said, leading the way to the kitchen.

“No. Just plain water.”

A little later, in the front room with our lemonade and plate of cookies and Daisy stretched out and half asleep on the floor near us, I picked up a book.

Near the end of the third chapter, Daddy and Mama came into the room. Daddy was in his blue jeans and white T-shirt and Mama was in her pink pajamas and pale green robe. She settled down on the recliner, and Daddy sat on the sofa.

Myra Sue and I looked at each other, then at our parents. Mama rested her head against the back of the recliner and closed her eyes as if she didn’t have the strength to keep them open a moment longer. I laid the book down, and my sister and I scrooched close together, grabbing each other’s hands.

“Girls,” Daddy said. “We want to talk to you.”

Mama looked into my eyes. Then she looked into Myra Sue’s. “Girls, you are so precious. Do you know that? God has blessed me and your daddy with the best daughters in the world. Hasn’t He, Daddy?” She looked around us at Daddy.

“He surely has.”

Even with all this praise and reassurance swimming around my sister and me like caramel goo, my imagination just wouldn’t let go of trying to solve the puzzle of why Mama didn’t look or act like herself.

I stared right into her face.

“Tell me straight out,” I said, then swallowed hard so I could force out my next words. “Are y’all gonna get a divorce? You and Daddy. Are you gonna split up? ”

I know it sounded like the craziest thing in the whole entire world. But I had to ask. Otherwise that very idea would trail me just like the fear of Mama’s death.

Mama’s eyes couldn’t have gotten any bigger if I’d pulled out Daddy’s electric razor and shaved every hair off my head.

“Of course not! I love your daddy and he loves me. You know that. We’d never split up.”

“That’s right,” Daddy said. He got up and grabbed one of Mama’s puffy hands and planted a kiss in her palm. “Your mama is stuck with me for the rest of her life.”

They smiled at each other. Boy, oh boy, how did I have enough imagination to even suppose such a thing as them breaking up?

“Well, girls,” Mama said, “how would you girls like another person living here?”

“Another person?” I repeated, mystified. “Like who?”

Myra Sue and I looked at each other, then back at our mother, and I continued, “We got the St. Jameses sleepin’ right down the hall. I think that’s enough, don’t you?”

Myra Sue was staring at Mama with her mouth wagging open like a dying fish. Then she shut it, gulped, and said in a strangled voice, “Mama? Are you . . . oh, Mother. Tell me no. You aren’t. Are you?”

Sometimes my sister is not the most articulate person on the planet. Or even in the house.

“We’re going to have a baby early next year,” Mama said, her full smile returning. “The doctor says sometime around the end of January or early February.”

While they looked at my sister and me, the two of us just sat there gawking back. Myra Sue blinked fast about a hundred times.

“A baby,” she repeated.

“Yes!” Daddy said with a grin. “What do you think of that?”

I couldn’t even think straight, let alone repeat that word.

All this time I had been worried and confused and scared out of my mind. Now I didn’t know what to think. I was gladder than you can imagine that Mama was not dying and that she was going to be fine, but . . . a b-b-baby?

Good grief.

Myra Sue and I exchanged a glance. I could see she had a hard time swallowing this crazy news, and I’m pretty sure my face looked the same way. A baby. In our house. For forever. It was just too much for a human child with a bratty older sister to take in.

I wanted to hurl and nearly did.

I finally found my voice. “Do you mean that having a baby makes you this sick?”

“This time, yes,” Mama said with a wan smile. She looked all pale and worn-out.

“Then why would you ever want one?”

“Well, honey, it was a surprise to us, too, but it’s a blessing. Your daddy and I are very happy. As happy as we were when we found out you were coming along, and Myra Sue when we were expecting her.”

I had nothing to say to that.

Ole Myra Sue’s face gradually went from disbelieving and

amazed to downright peculiar. I thought maybe she was getting sick, too, so I moved back in case she decided to lose her lunch in my direction.

She stood up. Stiff and straight as a flagpole, she blinked about twelve times, and then she gave our mama a sour little smile.

“I am so glad you aren’t seriously ill, Mother,” she said, so prissy it would make your gizzard curl right up, “and I hope that you will feel better soon.”

She kissed Mama’s cheek with the very tips of her pooched-out lips, then she walked like a robot out of the living room.

“Myra Sue Reilly!” Daddy said in a Tone of Voice he reserved for dreadful times such as these when anyone could see he was ticked off good and proper.

Mama, looking pale and confused, turned to me.

“April Grace, honey, what else do you have to say?”

It was kind of hard to think of anything at all except I still felt like I might be sick any second. I reckoned I might feel that way for a few years or until that baby grew up and moved out.

“I don’t know what to say,” I managed to get out.

“Don’t you think you’ll like being a big sister?”

I felt my eyes get all big and buggy, ’cause that was something I hadn’t even thought of. Having been the little sister all this time and having been subjected to Myra Sue’s meanness, I didn’t want to be the older one if it meant I’d act like her. Being a drip has never been one of my goals.

“When it gets here, will I change?” I asked.

Mama frowned a little. “What do you mean?”

“I mean, will I have to be all snotty and snippy and bossy and pushy like Myra Sue? Is it required to act like a complete ignoramus to be a big sister?”

“Oh, April Grace,” Daddy said, and

I could tell by his voice that he was right disappointed with my answer. But, good grief, if they don’t want to hear what you think, they shouldn’t ask. That’s my motto.

“You and your sister are two different people,” Mama said. “You aren’t going to change a bit.”

“No, you won’t. But you might change a diaper,” Daddy said, joking.

“Diapers? Wet, poopy diapers? Me? No, sirree, thank you very much!”

“I’m really going to need your help, honey,” Mama said, coaxing.

Well, I was aghast and agog with this whole unrolling saga, so I spoke up again, even though I figured the adults weren’t going to like what I had to say.

“Mama, I’m happier than I can say that you are all right and not severely sick. You had me plenty worried.”

She gave me a soft little smile, but I plunged on.

“But I have to tell you the honest truth: I think having a baby in this house is not a good idea. It’s gonna change everything around here. And it isn’t like a baby will be moving into its own house, like the St. Jameses are gonna do someday soon, I sincerely hope. Plus, getting sick like you’ve been . . . and all cranky and moody . . . Well, it just doesn’t seem worth it, Mama. I wish you had talked with me before you decided to be pregnant, and I would have told you it was not the best thing you could’ve done.”

After I said all that, it got so quiet in the front room you could hear the yellow wall clock in the kitchen ticking away.

“I see,” Mama finally said.

“April Grace,” Daddy said, his voice low and quiet like when he gets riled. The way he got riled at Myra Sue a minute ago. I reckoned I’d just made it worse.

“No, Mike,” Mama said. “The girls have a right to feel the way they feel. It’s been just the two of them for a long time.”

“But, Lily—”

“It’s all right, Mike.”

A minute or two passed, and nobody uttered a mumbling word.

“It’s okay,” Mama repeated softly. “They’ll get used to the idea.”

She said it, but I didn’t hardly see how we would.

NINE

How Myra Sue Spells Humiliation

Cliques, Hicks, and Ugly Sticks

Cliques, Hicks, and Ugly Sticks In Front of God and Everybody

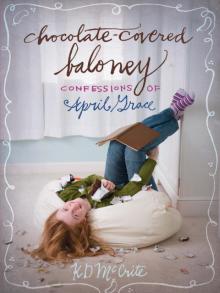

In Front of God and Everybody Chocolate-Covered Baloney

Chocolate-Covered Baloney